Hello everyone,

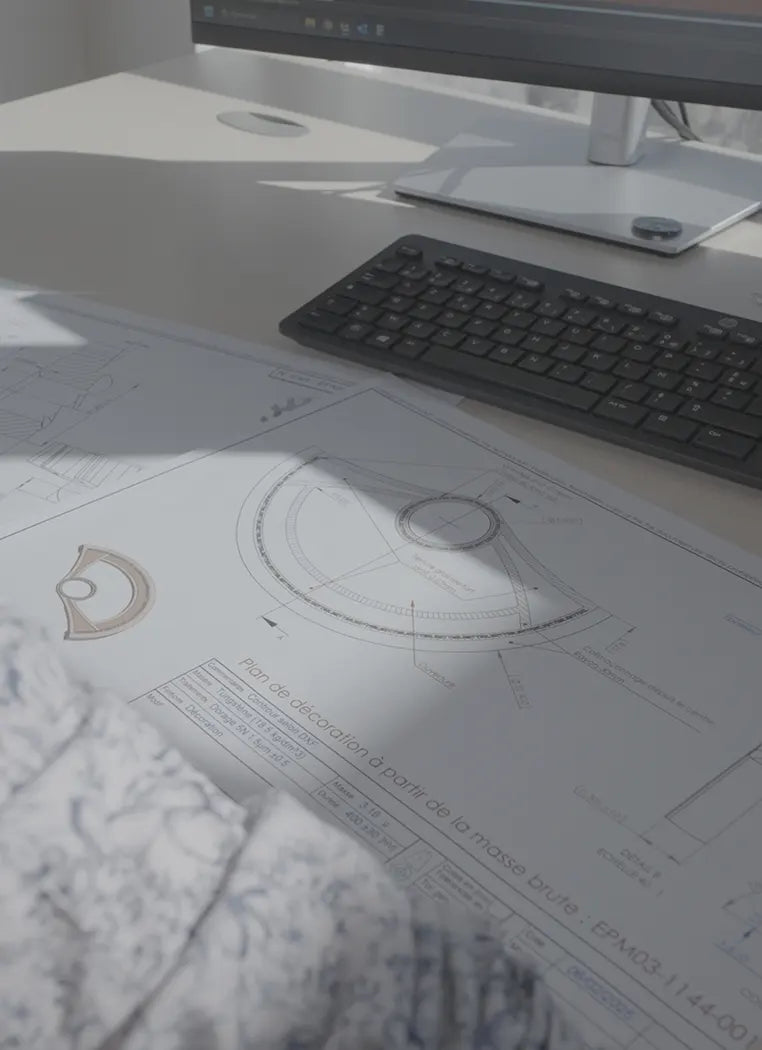

In our last article, we gave some background about handmade guilloché and about what it takes to make a Perception dial. As a reminder, those will be hand crafted using a rose engine by Master Cheng, China’s and Asia’s sole guilloché master craftsman. He needs 8 hours to create just one dial, and if you have not read the article, I encourage you to have a look here.

Today, we will tell you more about Master Cheng’s incredible life story.

Born in a poor family, Cheng unfortunately did not show any inclination for studies and was therefore quite bad at school. The combination of his family’s poverty and his own lack of academic abilities led him to drop out early, around the age of 14. Facing pressure from his parents to contribute to the household’s finances, he moved to Beijing in order to look for employment. He worked odd jobs across many different factories, with none of his contracts ever lasting very long. Precarity, you name it.

A breakthrough occurred when he went into doing an apprenticeship at one of the precision instrument manufacturing departments of the army. Coupled with another apprenticeship hosted by the training centre of the local Beijing Prison 5807 (!), Cheng had now acquired all the skills necessary to become a qualified, specialised factory worker. He had been an apprentice until 30, but finally, there he was. He was about to get out of poverty. He found a rather well-paid machinery job, got married, and a few years later, had some children. The story could have ended there: a nice happy ending for a rural child from a poor family who had “made it” in his country’s capital city.

But if this were the case, there would be no Perception at all and we would not be here today writing these words. One does not become a continent’s sole master craftsman of a rare métier d’art easily, or by chance. It does take an enormous amount of effort and hardship to reach such an unusual achievement, especially when absolutely no one else had historically ever done it. Cheng’s life was about to get disrupted. Profoundly so.

The Butterly Effect is a phenomenon I was only familiar with through Eric Bress’ eponymous 2004 film, but what happened with Cheng’s life is a real-world embodiment of the philosophical concept. One day, in 2014, when everything appeared stable in Cheng’s life, an old acquaintance of his came to the factory where he was working and invited him for lunch so that the two friends could catch up. Towards the end of the meal, he negligently took out an old Russian tobacco box and showed it to Cheng, introducing the item as his latest antique trouvaille. The box had a gorgeous wavy radial pattern guilloched, flinquéd with a layer of blue enamel. The way it reflected light and displayed depth was unlike anything Cheng had ever seen in his life, causing him to fall under the item’s spell. Being completely unfamiliar with its nature, his collector friend gave him a short introduction to guilloché, ending his speech by stating that strictly no one in China had ever done it.

Cheng felt something odd when looking at the tobacco box. It was almost surreal, as if the engraved pattern and the optical illusion it delivered was “physically” impossible. His fascination was sudden, instant and intense, and for a reason he still, to this day, cannot explain, he felt happy. At this stage, to fully understand why Cheng decided to take a leap of faith and embark on a journey to master guilloché, you need to know something about him: he is a proud and highly confident person, almost in a bold, defiant way. And it is understandable why his nature is this way: he had beaten the odds; he was an undereducated poor child from a rural area who had managed to build a pleasant life in Beijing when many of his classmates, relatives and friends were still living in poverty back home. He felt he could achieve anything, and thinking about how proud his relatives and himself would be if he became the first Chinese guilloché master craftsman gave him the final push he needed to fall down the rabbit hole.

Almost overnight, he decided to leave pretty much everything he had, including his job, to focus on his newfound interest. He set aside around RMB 350,000 (c. USD 55,000) i.e. close to his entire life savings and set sail to Xinmi and its suburbs, a modest-sized city (c. 800k inhabitants - not substantial by China’s standards) in Henan, 700 kms away from Beijing. There is not much to do in Xinmi; besides some Bronze Age archeological sites, the city is mainly residential and lives in the shadows of Zhengzhou, the province’s capital. Quite a far cry from Beijing’s glitter, opulence and endless attractions. This relative quietness is precisely what Cheng needed: a place with no distraction at all so that he could fully immerse himself into guilloché. He went a step further by setting up his atelier in a cave in a nearby mountain. The lack of distraction would be absolute and the absence of vibrations would allow him to perform at his best. Absolute, I feel, is the best adjective to describe his endeavour. He rented a nearby house, and needless to say that everyone he knew, including his wife, thought he was crazy. Cheng was 35, and he very well knew he would not make any money until he is 38 at least. His stint out of the poverty zone had been short, but there you can see his true craftsman spirit: a pure, ideal dedication to the craft, almost bordering obsession.

When Cheng decided to take the plunge, he mistakenly believed doing guilloché would be rather straightforward, but he was soon to discover how far away from truth his gut feeling was.

His first step was to attempt to create his own rose engine (rose engines are not made anymore and antique ones hardly ever come for sale (and even less so in China)). Never having seen one such machine by himself, not knowing how to use the internet back then, and not having access to any sort of textbooks explaining how to build them (those do not even exist anyway), the task was extremely challenging. After one year, a first fully handmade machine with a design that was 100% Cheng’s was ready, yet, as expected, it did not work at all. He had given it his all, but the result was, objectively-speaking, a failure. He had spent a year working 16 hours a day, 7 day a week, only taking short breaks to eat cheap instant noodles, and despite these tremendous efforts, on the eve of Chinese New Year, he was there, in his cold courtyard, standing next to a piece of scrap, a failure.

When most people would have given up and, reasonably so, gone back to their routine, comfort, and relative safety, Cheng persisted. By 2016, he had built two extra rose engines, which, although slightly better than his first design, were still plagued by a high number of issues, making them inherently unusable. The total number of machines he failed therefore jumped to 3.

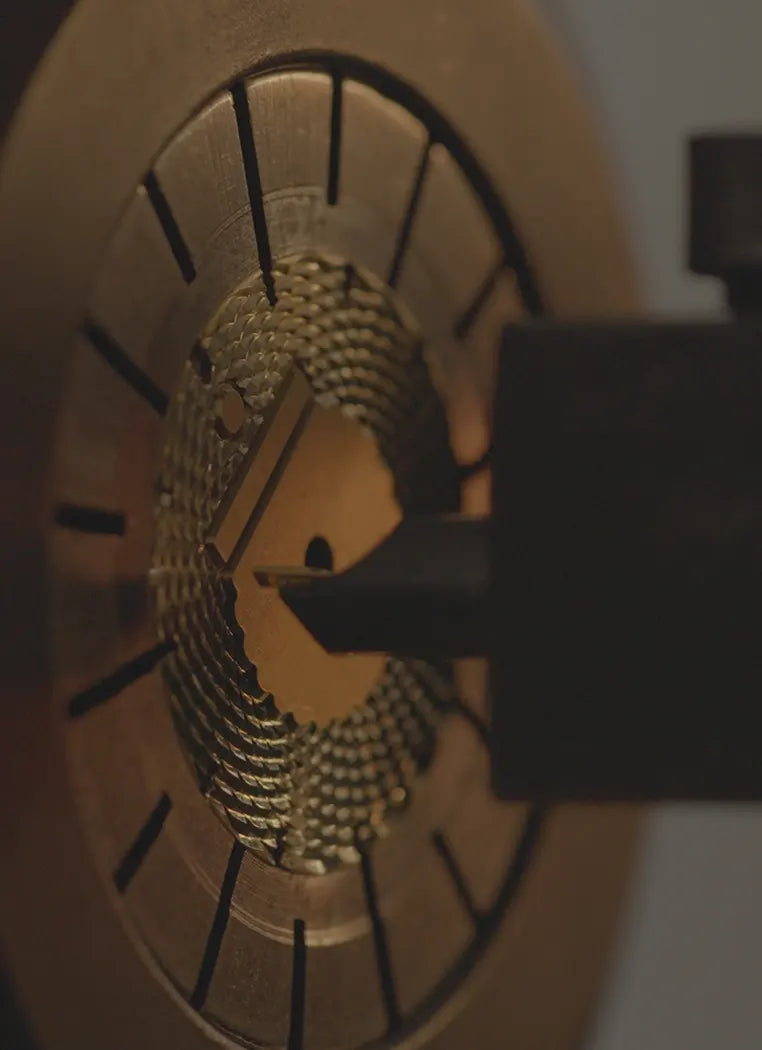

He still did not stop and pursued his endeavour. In 2018, after two years of extra efforts, he finally completed his first working machine. The design is 100% his, and 90% of the components were fully handmade by Cheng… A sizeable achievement! While he could have, Cheng did not stop there, and kept on building machines, continuously improving his craft. By 2021, he had completed his 7th machine, and 4th working one. Those are either rose engines or straight-line engines (they can engrave solely either horizontal or vertical patterns), and, together, these 4 machines enable him to engrave more than 1,000 patterns.

Cheng’s sole interest lies in guilloché. When asked whether one day he will want to create a brand or some complete watches, he replies that he is not interested at all. All he desires is to make increasingly better guilloché, and to, one day, have his craft in the same category as the métier d’art “masters” i.e. Comblémine and Metalem. He is also dreaming of making the field more popular in China, providing opportunities to young people who otherwise would be facing the same hurdles as he did. It is nevertheless hard to find apprentices as few young students want to live in the mountains, work extremely hard and stay focused for hours on end. Doing guilloché is very tiring and difficult, and to be successful, one needs to have a huge amount of grit and perseverance. It is tough to find young individuals who, despite their age, are mature enough to commit to these sacrifices.

Cheng currently has 4 apprentices, one of whom has been with him for 3 years. Down the line, he does not want more than 10 of them. He finds those apprentices from a nearby school where he teaches Machinery every Monday.

Since a journalist named Liu Xingli wrote an article about him in 2018, Cheng is getting orders through Beijing-based middlemen who then send the dials to Switzerland. Cheng is, of course, never acknowledged in the process, always staying in the shadows and the Swiss brands presenting the dials as their own creations.

Cheng’s work has also never been used in a locally made watch. With Perception, it will be the first time this happens.